Excerpt from William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation - Harvest of 1621

- Date

- C. 1630

- Material

- William Bradford

- Author/Maker

- William Bradford

- Source

- Of Plymouth Plantation

This image is provided courtesy of State Library of Massachusetts

Description

In the 1630s, William Bradford offered his own perspective on the bounty of the 1621 harvest, listing many of the foods that were available during the harvest celebration. Perhaps the strongest connection between the 1621 harvest celebration and later Thanksgiving celebrations is that both menus are based on seasonally-available foods with New England roots. The presence of venison, hunted and brought back to New Plymouth by Ousamequin’s men, was significant.

Both cultures enjoyed it. In England, however, venison was rarely part of a common person’s experience. In England, deer were found only in the parks and forests of the landed gentry. Venison was not commercially available; by law, you could not buy or sell it. On the other hand, deer was central to the Wampanoag way of life in the 17th century, providing not only meat, but other materials for clothing and tools. Men were responsible for providing their families with meat and fish, spending fall and winter hunting large animals such as deer. Colder months were better not only for the furs, but also because most animals are not bearing their young at that time. If deer were hunted at other times of year, care was taken to obtain only bucks. Ousamequin’s presentation of five deer to the English leaders was essential to the diplomacy as well as the meals taking place during the three-day event.

Like venison, wildfowl were also considered a celebratory food though they were eaten throughout the year. Winslow writes that in one day, four Englishmen “killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week."1It is likely or almost certain that the feast featured turkey. Governor William Bradford noted that there was a “great store of wild turkeys”2 Thousands of migratory ducks and geese are found in the region each fall, and smaller birds, such as quail and the now-extinct passenger pigeon, may have made an appearance on the table in 1621 as well.

Contemporary sources note the plentiful fish, including cod and sea bass, the communities enjoyed throughout the late summer and fall of 1621. In mid-September, Bradford wrote that those men who stayed close to home that summer “were exercised in fishing, about cod, and bass, and other fish of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion; all the summer there was no want.” Mussels, lobster, and eel were available throughout the fall as well. Both the English and Wampanoag enjoyed these fruits of the sea; it is possible that Indigenous and English women saw one another along the marshes and beaches gathering the abundant food.

Many historians wonder why William Bradford, writing at least a decade later, did not mention the harvest celebration.

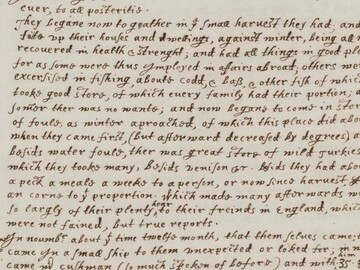

Transcription

They began now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fit up their houses and dwellings against winter, all being well recovered in health and strength and had all things in good plenty. For some were thus employed in affairs abroad, others were exercised in fishing about cod, bass, and other fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl there was a great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides they had about a peck a meal of week to a person, or now since harvest, Indian corn to that proportion. Which made many afterwards write so largely of their plenty here to their friends in England, which were not feigned but true reports.3

Media

Read the Excerpt

View PDFTranscription

They began now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fit up their houses and dwellings against winter, all being well recovered in health and strength and had all things in good plenty. For some were thus employed in affairs abroad, others were exercised in fishing about cod, bass, and oher fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl there was a great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides they had about a peck a meal of week to a person, or now since harvest, Indian corn to that proportion. Which made many afterwards write so largely of their plenty here to their friends in England, which were not feigned but true reports.

Discussion Questions

-

How does Bradford’s account of the 1621 harvest compare to Winslow’s? What details did Bradford include that Winslow did not?

-

Why do you think the authors made the choices they did about what details to include? What does Bradford’s recounting tell us about how the harvest celebration was remembered 10+ years later?

Footnotes

- 1 Mourt’s Relation: a Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, ed. Dwight B. Heath. (Applewood Books, 1963), pg. 82

- 2 William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation. (Boston: Conserved and digitized by the State Library of Massachusetts, 2014), 65 during the fall of 1621.

- 3 William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation. (Boston: Conserved and digitized by the State Library of Massachusetts, 2014), 65