Primary Sources

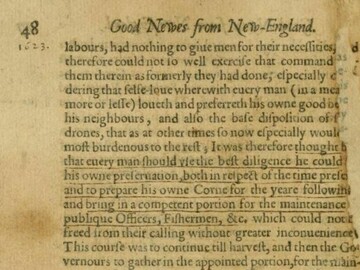

This Unit aligns with the Document Decoder - 1621 harvest celebration (Activity 4) in the "You are the Historian" Interactive Game.

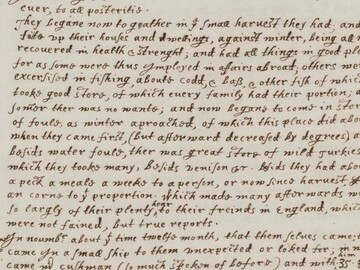

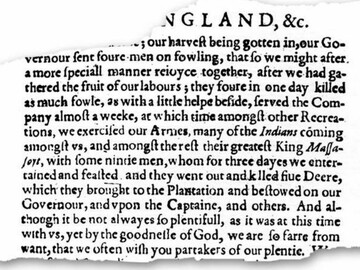

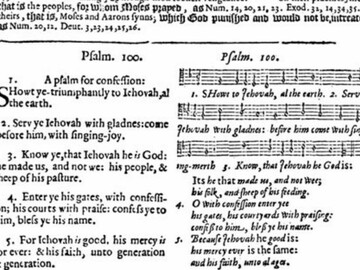

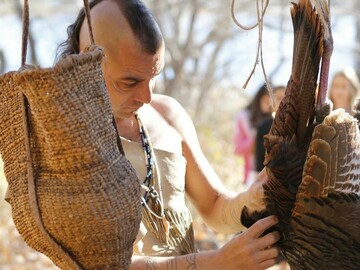

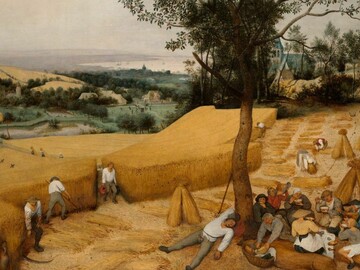

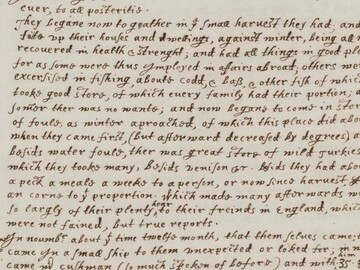

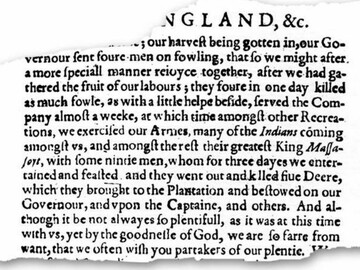

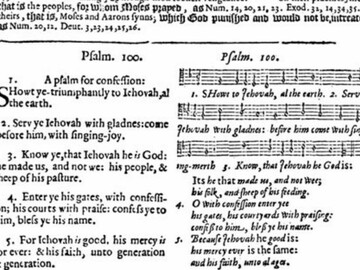

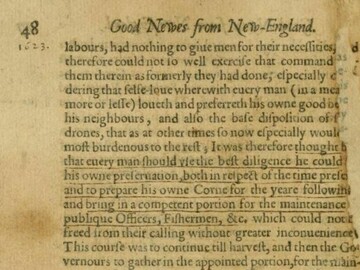

Learning Themes:In this unit, students will investigate the only surviving eyewitness account of the 1621 harvest feast and use other complementary sources to deepen their understanding of the spiritual world views, particularly around gratitude, which formed the foundation of events over the three days. Students will also explore how the 1621 harvest feast came to be known as the First Thanksgiving over the next 200 years and how the meaning of the holiday changes as new meaning is layered.

In this unit, students will:

Grades K-5

Grades 6-12

How do we commemorate our shared history as a nation and community?

How did Native Peoples live in New England before Europeans arrived?

What were the challenges for women and men in the early years in

Plymouth?

How did the interactions of Native Peoples, Europeans, and enslaved and free Africans shape the development of Massachusetts?

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

Identify key steps in a text's description of a process related to history/social studies (e.g., how a bill becomes law, how interest rates are raised or lowered).

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies.

Describe how a text presents information (e.g., sequentially, comparatively, causally)

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author's point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic.

Analyze in detail a series of events described in a text; determine whether earlier events caused later ones or simply preceded them.

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or economic aspects of history/social science.

Compare the point of view of two or more authors for how they treat the same or similar topics, including which details they include and emphasize in their respective accounts.

Integrate quantitative or technical analysis (e.g., charts, research data) with qualitative analysis in print or digital text.

Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources.

Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

Evaluate authors' differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors' claims, reasoning, and evidence.

Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text and explain how it is conveyed in the text.

Compare and contrast one author's presentation of events with that of another (e.g., a memoir written by and a biography on the same person).

Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

Analyze the interactions between individuals, events, and ideas in a text (e.g., how ideas influence individuals or events, or how individuals influence ideas or events).

Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author distinguishes his or her position from that of others.

Analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic shape their presentations of key information by emphasizing different evidence or advancing different interpretations of facts

Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

Analyze how a text makes connections among and distinctions between individuals, ideas, or events (e.g., through comparisons, analogies, or categories).

Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author acknowledges and responds to conflicting evidence or viewpoints.

Analyze a case in which two or more texts provide conflicting information on the same topic and identify where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation.

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

Analyze how the author unfolds an analysis or series of ideas or events, including the order in which the points are made, how they are introduced and developed, and the connections that are drawn between them.

Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how an author uses rhetoric to advance that point of view or purpose.

Analyze seminal U.S. documents of historical and literary significance (e.g., Washington's Farewell Address, the Gettysburg Address, Roosevelt's Four Freedoms speech, King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail"), including how they address related themes and concepts.

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

Analyze a complex set of ideas or sequence of events and explain how specific individuals, ideas, or events interact and develop over the course of the text.

Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem.

Analyze seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century foundational U.S. documents of historical and literary significance (including The Declaration of Independence, the Preamble to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address) for their themes, purposes, and rhetorical features.

Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

Acquire and use accurately general academic and domain-specific words and phrases, sufficient for reading, writing, speaking, and listening at the college and career readiness level; demonstrate independence in gathering vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.