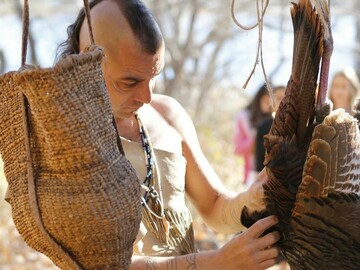

“Great store of wild turkeys…”

- Date

- 2015

- Material

- Photograph

- Author/Maker

- Plimoth Patuxet Museums

- Source

- Plimoth Patuxet Museums

Description

In 1827, when Thanksgiving advocate Sarah Josepha Hale wrote what is thought to be the first literary description of Thanksgiving, she gave roasted turkey “precedence on this occasion, being placed at the head of the table.” In 1841, when Alexander Young included the eyewitness account of the 1621 harvest feast in his Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers, he footnoted the event as “the first Thanksgiving.” He added, likely drawing on his own 19th-century experience of Thanksgiving as much as the details in the 17th-century source, “On this occasion, they no doubt feasted on the wild turkey as well as venison.”1

But was turkey really on the table in 1621? Although we can’t say for sure, it seems very likely. To answer the question, we examine evidence of the prevalence of turkeys in 17th-century New England, the uses of turkey in both English and Indigenous life, and sources mentioning the natural abundance of the fall of 1621.

The eastern wild turkey, Meleagris gallopavo, is native to North America. Common in New England in the early 17th century, it was found along the Atlantic seaboard from Ontario to the northern reaches of Florida and into the midwest. Black or brown with white bars on its wings and strikingly lustrous tail feathers, the eastern wild turkey is one of six subspecies of wild turkeys, whose habitats, collectively, span nearly the entire North American continent.2

Indigenous historians note that turkeys were hunted throughout the year in the 17th century, prepared either by roasting on spits or boiled in stews and soups. At the wedding of Governor William and Alice Bradford in August 1623, Ousamequin brought a turkey, in addition to three or four bucks3Turkey feathers are still woven into garments by Indigenous women. According to Nanepashemet (Assonet Wampanoag), former head of Plimoth Patuxet’s Wampanoag Indigenous Program, “A most spectacular type of clothing, frequently noted by Europeans, was the feather mantle...woven with native-made twine with the feathers fastened into the weaving.” English colonist Roger Williams compared the iridescent sheen of the interlocking layers of feathers to European velvet.4

Before the Spanish arrived in Central America, the Aztec people had long been breeding the ocellated turkey (Meleagris ocellata) as a delicacy for the aristocracy.5The first mention of turkeys in Europe appears to be a 1511 letter from King Ferdinand of Spain requesting turkeys to be sent from the West Indies to Seville for breeding.6

In an age of extravagant banqueting, turkeys achieved almost immediate popularity in Europe as a more palatable substitute for the peacock. In the Middle Ages, when roasting an impressive bird like a peacock, chefs saved the feathers and head to reattach to the bird’s body after roasting for an awe-inspiring table presentation. The ostentatious feathers of the turkey worked equally well for this, and as an added bonus, the flesh of the turkey was far more succulent and tender than that of the peacock.7

When, exactly, the turkey arrived in England is a matter of some speculation. William Strickland, a member of a transatlantic expedition in the 1520s, is often credited with bringing the first turkey back to England. He later adopted a family crest featuring a turkey, possibly the first visual depiction of the bird in Europe.8 Although there is little evidence to support this story, butchered turkey bones dating between 1520 and 1550 were found in archaeological excavations beneath the modern city of Exeter in 1983.9

Before the end of the 17th century, the turkey’s place in European gastronomy was firmly established. European domestic breeding had transformed turkey from an exotic banqueting marvel to a ubiquitous barnyard fowl.10 They were rapidly becoming popular for English Christmas tables. Writing in the mid-16th century, poet Thomas Tusser included a “turkey well dressed” along with beef, capons and mince pies in his description of a proper Christmas table.11Most period recipes for poultry indicated they were suitable for any type of fowl, including turkeys. Turkey-specific recipes began to appear infrequently in the late 16th century, including “To make sauce for capons or turkey fowles'' or “To bake turkey fowls'' inA Booke of Cookery (first published 1584) and “To Bake a Turkey and take out his bones” in Thomas Dawson’s The Good Huswifes Jewell (first published 1585). A popular example at Plimoth Patuxet, Gervase Markham’s “Sauce for a turkey,” is included in “Manners and Menus.”12

Due to their growing popularity in Europe, the five women who survived the first winter at New Plymouth may have had some culinary experience with European domesticated turkeys. In 1621, they must have gained experience with their wild counterparts. Sources suggest wild turkeys were ubiquitous throughout the region in the first half of the 17th century. William Wood wrote in New England’s Prospect (1634), “sometimes there will be forty, threescore, and a hundred of a flocke, sometimes more and sometimes less.”13Three men who visited Plymouth at various times in the 1620s mention turkeys in their surviving description of the colony.14

They were almost certainly on the table at the harvest celebration in 1621. According to the only eyewitness account, four men were “sent on fowling” in preparation for the festivities, returning with enough supply to feed the fifty Plymouth colonists for almost a week. Fowling is the act of shooting, trapping or snaring fowl. In the 17th century, “fowl” was a loose term used most commonly to refer to a “winged vertebrate animal,” or somewhat less frequently, any creature with wings.15 Period writers considered turkeys to be fowl. English writer William Wood described the natural and cultural landscapes of New England, including the turkey, in his chapter on “the birds and fowles both of land and water.”16

In his description of their first harvest, Governor William Bradford includes turkeys in the bounty of the fall of 1621, writing “All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they first came (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl, there was great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc.”17 Turkeys and venison went hand-in-hand in describing the abundance of their first autumn in New England.

Writing more than a decade after the events in question, Bradford’s parenthetical note alludes to something else: the turkey’s popularity and the overhunting that decimated the population by 1640. By 1672, English writer John Josselyn remembers “threescore broods of young Turkeys on the side of a Marsh, sunning themselves in a morning betimes, but this was thirty years since, the English and the Indian having now destroyed the breed, so that ‘tis very rare to meet with a wild Turkey in the Woods; but some of the English bring up great store of the wild kind, which remain about their Houses as tame as ours in England.”18 The domesticated turkey was becoming more and more popular. Although the last wild turkey native to Massachusetts died in 1851, wildlife biologists successfully released thirty-seven birds from New York in the 1970s. In 1991, the wild turkey was named the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ official state game bird, and today, population estimates exceed 25,000. As game birds, their numbers are managed through careful hunting.19

The turkey continues to captivate us as a symbol of America’s place in the world. Though the letter in which it was included remained unpublished until 1817 and was more about the establishment of the Society of the Cincinnati after the American Revolution than any exposition on the new nation’s avian life, Benjamin Franklin’s characterization of the turkey is accurate. “For in truth,” he wrote in 1784, “the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and with a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours.”20 Though most turkeys we eat today are domesticated, wild turkeys staring us down on the road or foraging in dewy fields on early fall mornings remain a reminder of their long history in New England.

Media

Still Life with Turkey Pie, Pieter Claesz, 1627, Oil on Panel.

Read an excerpt from Pierre Belon's Histoire de la nature des Oyseaux

View PDFTranscription

DES OYSEAVX, PAR P. BELON.

Femblable au Coc d’Inde, finon que l’vne porte la crefte, & les barbillons rouges, qui au Coc d’Inde font de couleur de ciel. Il eft tout arrefté que tout autheurs parlants du Coc d’Inde, que maintenos eftre Meleagris, ont dit quils font tachez de diuerfes madrures. Ces Cocs d’Inde ont vn toffet de poils durs, gros, &noirs en la poictrine, refemblants à ceux de la queue d’vn Cheual, defquels cefroit à

Melegris en Grec, Gibberen Latin, Coc d’Inde en Francoys.

S’fmerueillé que les autheurs anciens Latins & Grecs neuffent point parlé. Tou-tesfois Ptolomee en la penultime table d’Afie en a fait fpeciale mention, le nom-mant Paon d’Afie. Pline a efcrit Meleagris, comme pour oyfeau de riuiere, duquel auons parlé au dernier chapitre du premier liure : c’eft la caufe que nous l’ayons efcrit entre les oyfeaux, qui nous font incognuz: car nous pretendons qu’il vous-loit entendre d’vn autre, que de noftre Poulle D’Inde.

Du Coc de bois, ou Faifant bruyant.

CHAP. XI

Il y a telle diftinction entre le mafle Coc de bois, & fa Poul-le, qu’entre noftre Coc priué, & la Poulle. Ce n’eft merueille fi les habitants des villes fituees aux pieds des monts, n’ont les Faifants fi communs, que ceux qui habitant en pais de plaine: qui toutesfois prenent grande quantité de Cocs de bois, qui nous font rares au plat paЇs de plaine: qui toutesfois prenent grande quantité de Cocs de bois, quit nous font rares au plat paЇs de Frace. La raifon eft que le naturel du Faifan luy enfeigne viure plus commodement par le paЇs plat, qu’à la mo-

Discussion Questions

-

Where do turkeys come from?

-

Have you ever seen a wild turkey? What did it look like? Draw a picture.

-

Who ate turkey in Aztec communities? Who ate turkey in Wampanoag communities?

-

How did turkeys get to Europe? Who brought them there and why?

-

Before turkeys were associated with Thanksgiving, which holiday featured “turkey well dressed?”

-

Benjamin Franklin wanted to make turkey the national bird. Do you agree? Why or why not?

Footnotes

- 1 Sarah Josepha Hale,Northwood; A Tale of New England, vol. I (Boston: Bowles & Dearborn, 1827), 109; Alexander Young, Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers, (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 231, n. 3.

- 2“Index of Special Information, Meleagris gallopavo,” Fire Effects Information System,”

- 3 .Emmanuel Altham to Sir Edward Altham, September 1623, in Three Visitors to Early Plymouth, ed. Sydney V. James, Jr. (Plymouth: Plimoth Plantation, 1963), 29.

- 4 Roger Williams, A Key into the Language of America (London: Gregory Dexter, 1643; reprint Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1997), 119.

- 5 Sabine Eiche, Presenting the Turkey: The Fabulous Story of a Flamboyant and Flavorful Bird (Florence: Centro Di, 2004), 11.

- 6 A.W. Schorger, The Wild Turkey: Its History and Domestication (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 464.

- 7 Bruce Thomas Boehrer, Animal Characters: Nonhuman Beings in Early Modern Literature, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 141.

- 8 Eiche, 17-18.

- 9 Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery, “Tudors Put Turkey on the Menu,” 20 December 2017.

- 10 Boehrer, 143.

- 11 Thomas Tusser,Five hundred points of good husbandry (London: Richard Tottill, 1573).

- 12 See A.W., A Book of Cookrye, (London: Printed by Edward Allde, 1591); Thomas Dawson, The Good Huswifes Jewell (London: John Wolfe for Edward White, 1587); Gervase Markham, Country Contentments, or the English Huswife (London: Printed by J.B. for R. Jackson, 1623), 89.

- 13 William Wood, New England’s Prospect (London: John Dawson for John Bellamy, 1634), 25.

- 14 See Three Visitors. Altham remarks on “innumerable turkeys, geese, swans, duck, teel, partridge divers sorts, and many other fowl” (28); Isaack de Rasieres notes the “very large turkeys living wild” (79) and John Pory observes “turkeys as large and as fat as in any other place” (11).

- 15 See "fowl, n.," OED Online, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, June 2021).

- 16 Wood, 23-24

- 17 William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation: A Facsimile of his Original Manuscript, (Plymouth, MA: Plimoth Patuxet Press, 2020), 77.

- 18 John Josselyn,New-Englands Rarities Discovered, (London: Printed for G. Widows, 1672), 8.

- 19Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, “Learn About Turkeys.”

- 20Benjamin Franklin, Passy (France), to Sarah Franklin Bache, 26 January 1784 Passy, Founders Online, National Archives. In The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 41, September 16, 1783, through February 29, 1784, ed. Ellen R. Cohn. (New Haven: Yale, 2014,), 503–511.