Memories of Thanksgiving Across the Centuries

- Date

- 1880, 1900, 1944, 1990

- Material

- Oral History

- Author/Maker

- Artist name is no longer known.

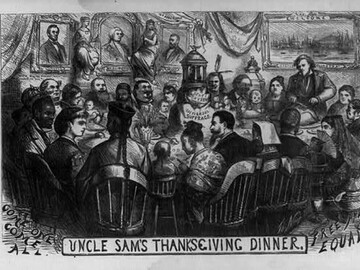

Thomas Nast, “Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner,” Harper’s Weekly, November 20, 1869. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. In 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship “to persons born or naturalized in the United States” and guaranteed citizens equal protection under the law, including people who had formerly been enslaved. In President Grant’s interpretation, it also included Native people, and in 1869, newly-appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely Parker (Tonawanda Seneca), became the first Indigenous American to hold a cabinet-level position. In the same year as Nast’s drawing, the Fifteenth Amendment granted the right to vote to all US citizens regardless of race. Responding to the ideals (if not always the practice) behind these legislative achievements, Nast’s 1869 Thanksgiving is one of great inclusion, even if it draws on some stereotypes we would consider offensive today. While Washington, Lincoln and Grant look on, a diverse group of Americans await the carving of the turkey around a centerpiece that reads “self governance” and “universal suffrage.”

Description

Oral History is the collection and study of historical information using interviews with people who have personal knowledge of past events. These excerpts from diaries, journals, interviews, and magazines describe a Thanksgiving celebration that happened during their life and what the holiday meant to them.

The first national Thanksgiving wa s proclaimed by the Continental Congress in 1777 as the American Revolution began to turn in favor of the colonies. A somber event, it specifically recommended “that servile labor and such recreations as, though at other times, innocent, may be unbecoming the purpose of this appointment, be omitted on so solemn an occasion.” National Thanksgivings were proclaimed by Presidents Washington, Adams and Monroe, but the custom fell out of use after 1815. In the 1830s, New Englanders looked back at the Pilgrims’ harvest feast and began to refer to it as the “First Thanksgiving,” because there were so many similarities between it and their own holiday—which featured morning church services, family reunions, sports, and turkey with all the trimmings. In 1837, Sarah Josepha Hale, a writer for and later editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book began a campaign to reinstate the holiday by petitioning governors and several succeeding presidents to make it an annual event.

In 1841, this movement was bolstered by the publication of Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers by antiquarian and minister Alexander Young. In the book, Young included the previously lost account of the 1621 harvest feast included in the letter by Edward Winslow. In a footnote, Young named the event “the First Thanksgiving.” Young even speculated about the probable menu that day, interpreting the reference to “fowl” as wild turkey. And in fact, Plymouth Colony governor William Bradford mentions the “great store of wild turkeys” available that fall of 1621. Young’s designation is the earliest known reference that mentions the First Thanksgiving by name. As the century progressed, the passage from Winslow became increasingly associated with the event in Plymouth.

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln set a long-standing pattern when he declared a Thanksgiving for the last Thursday in November. That day would continue to be set aside by presidents every year from 1864-1939.6 In 1939, when the last Thursday landed on the final day of the month, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the holiday back a week to extend the Christmas shopping season. Two years later, Congress passed a law that permanently established Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday of November.

Over the last several decades, regions in Florida, Texas, Maine, and Virginia have declared themselves the site of the First Thanksgiving. Historical documents do not support the idea of a harvest feast but rather that religious observances were held in each of these places. Spanish explorers in Florida and other English colonists in Virginia, for example, celebrated religious services of thanksgiving years before Mayflower arrived. These other thanksgivings were prayer ceremonies that occurred once and were quickly forgotten long before the establishment of the American holiday. Few people knew about these events until the 20th century, and they played no role in the evolution of Thanksgiving. As James W. Baker states in his book, Thanksgiving: The Biography of an American Holiday, “despite disagreements over the details,” the three-day event in Plymouth in the fall of 1621 was “the historical birth of the American Thanksgiving holiday.”

Similar confusion around the differences in thanksgivings and Thanksgiving have led people to designate events that occurred even after 1621 as the root of the current Thanksgiving holiday. Internet meme culture has promulgated a number of mistaken identities for the First Thanksgiving. Recently a misleading story resurfaced that the First Thanksgiving was in response to the massacre of Pequot people in 1637. Religious days of thanksgiving (lowercase t) were, indeed, held in Boston, Scituate, and Connecticut to mark often-tragic events in the Pequot War, but like the other claims, they were prayer ceremonies and not the harvest feast that influenced the creation of the national Thanksgiving holiday.

Americans around the world continue to observe Thanksgiving each year. Most of these celebrations joyfully continue the tradition begun four hundred years ago in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Service members stationed in faraway lands, American expatriates starting a new life, world travelers, and students stop to reflect and observe the holiday. It is a time of gratitude, of celebrating family and friends, and a moment for Americans to come together to consider the important lessons from the Nation’s origins. Every year, Americans gather together bringing their own traditions to the feast.

Transcription

Nettie McCormick Henley - 1880s: Rural North Carolina

The Home Place (1989)

(Laurinburg NC: St. Andrew’s Press, 1989)

“I was born in 1874 and the time I speak of was from then till 1904 when I married and moved away from the Home Place. The North Carolina community where I grew up was in a good stretch of farmland which was then the eastern section of Richmond County…We never had any special dinner on Thanksgiving. Everybody worked all day just like any other day. It seems to me that our table was loaded down every day with about as much as most people have on Thanksgiving nowadays. We did not stop work to be thankful, but we were thankful every day for what we got. We always killed a hog before Thanksgiving and there were ham and sausage and liver pudding being eaten every day along that time of the year. It was, old folks said, a Yankee idea to be thankful on just one day of the year.”

Elizabeth Stern - c.1900 New York City

My Mother and I (New York 1917)

Quoted in Andrew Heinze, Adapting to Abundance (New York, Columbia University, 1990)

“Elizabeth Stern…whose family emigrated from Russia to New York City in 1892…remembered how Thanksgiving was adopted in her home. As the children grew up and began to speak English at home, their parents tried to adapt to some American ways. One Thanksgiving, Stern’s father brought home a turkey, which her mother repeatedly compared to a duck and a chicken, the poultry that Jews had traditionally employed on holidays and festive occasions. In a further blending of American and Jewish features, the table was set with a white cloth, ‘as if it were a holy day,’ and her father, who made a meager living teaching Hebrew, recited tales from the Talmud. Afterward, young Stern explained the meaning of Thanksgiving. Her mother responded with approval, but managed to give Judaism the last word by reminding the inquisitive daughter that ‘one must not give thanks on one day and for one bird!’”

Gene Currivam - 1944: Somewhere in France

“Hot Turkey Cheers the Third Army Squad,” New York Times (Nov. 24, 1944)

“Back from foxholes knee deep in water camp a quad of the 155th Infantry that had been relieved for the occasion [Thanksgiving]... These boys headed straight for a burned-out barn where, they had been told, they could make a rendezvous with a meal truck… Promptly at 11:30 a truck pulled up in front of the barn with great steaming cases of food. While it was being unloaded, the GIs started a fire in the barn and brewed their own coffee. Then they lined up with their mess kits and one of the great moments of the year was at hand. Their eyes literally popped when they saw the generous portions and unexpected variety. There were large slabs of turkey, a mound of potatoes with savory gravy, carrots, peas, raisin bread, butter, cookies and candy. And each man got a cigar.”

Seaman “Buzzy” Turner (Mashpee Wampanoag)

Interviewed for Plimoth Patuxet Museums, Thanksgiving: Memory, Myth, and Meaning Exhibit (c.1990)

“To me Thanksgiving is every day. I think especially when you get to be my age, if you can get out of bed and go through the day without any problems, that’s Thanksgiving. Years ago, Thanksgiving was a time when out family all came together. We sat down and had a big dinner, and reminisced about the old days, but those days are gone as for most of my family are do far separated and the elders are just about all gone. Now I look forward to every day because every day is a Thanksgiving to me.”

Media

William St. John Harper, “Castle Garden - Their First Thanksgiving Dinner,” Harper’s Weekly, November 29, 1884. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division The artist portrays an immigrant family eating together at Castle Garden in New York City, the forerunner to Ellis Island.

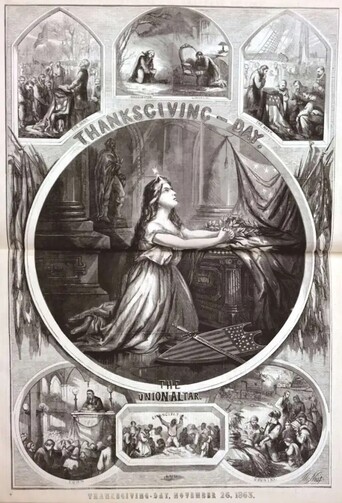

Thomas Nast (1840-1902), “Thanksgiving Day Scenes: The Union Altar,” Harper’s Weekly, December 5, 1863. Guilder Lehrman Institute. Accessed online. Throughout his long career, German-born illustrator Thomas Nast depicted Thanksgiving for Harper’s Weekly readers in many different ways. His interpretations reflect the ways we continue to draw on and comment on the present through the lens of the Thanksgiving holiday. Here, Nast depicts Columbia, the personification of the United States kneeling before an altar inscribed with the word, “union.” Columbia looks up at Presidents Washington and Lincoln facing one another, as if drawing a connection between the Thanksgiving of November 1789 and the one proclaimed by Lincoln and celebrated just a week before. The bottom of the illustration depicts people in rural and urban settings giving thanks, and, perhaps in reference to the newly-established Emancipation Proclamation, a group of formerly enslaved people under the banner “Emancipation.”

Discussion Questions

-

How are these accounts of Thanksgiving similar? How are they different?

-

What stories do these images tell about Thanksgiving? How are they the same or different to what Edward Winslow and William Bradford wrote about the event?

-

How did the 1621 harvest feast evolve into the annual national day of thanksgiving we celebrate today?

-

How has the meaning of Thanksgiving changed over time from the 1830s to the 1930s and today?

-

How does gratitude play a role in the many thanksgivings we celebrate?