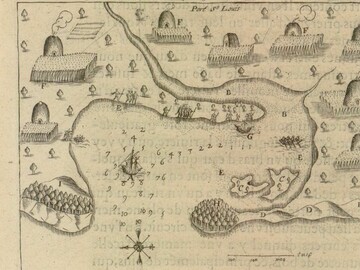

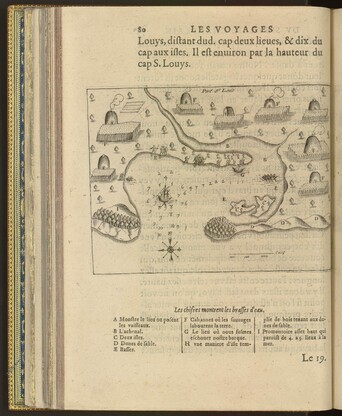

Port St Louis

- Date

- 1605

- Material

- Map, Engraving

- Author/Maker

- Samuel de Champlain (1567? - 1608)

- Source

Les Voyages du Sievr de Champlain Xaintongeois, 1613.

Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Description

Shortly after the voyages of Christopher Columbus (1492) and John Cabot (1497), encounters between peoples of Europe and the Americas led to an understanding on both sides of the Atlantic that there were other people in previously unknown parts of the world. The Indigenous nations along the coast of southern New England had interacted among themselves for thousands of years before the first Europeans came. Around the year 1500, French, Dutch and English fishermen and fur traders began trading with Indigenous people. The presence of these newcomers changed the way Native peoples related to each other. Sachems began competing for the most advantageous trade in furs, causing intense rivalries.

French explorer Samuel de Champlain’s map of “Port St. Louis” from 1605 is the earliest known European representation of Patuxet, the Wampanoag community that became the site of Plymouth Colony and which the Herring Pond Wampanoag still call home today. The name “Patuxet” has several possible translations including “place of little falls” and “place of little springs.” At the time of Champlain’s visit to Patuxet, the population numbered approximately 2,000 people. Families cultivated corn, beans, and squash in their gardens, gathered food, and came together for political and social meetings. In his book, The Voyages of Samuel de Champlain (1613), the author described the encounter depicted in this map. Here is an English translation from the original French:

The same day we sailed two leagues along a sandy coast, as we passed along which we saw a great many cabins and gardens. The wind being contrary, we entered a little bay to await a time favorable for proceeding. There came to us two or three canoes, which had just been fishing for cod and other fish, which are found there in large numbers. These they catch with hooks made of a piece of wood, to which they attach a bone in the shape of a spear, and fasten it very securely. The whole has a fang-shape, and the line attached to it is made out of the bark of a tree. They gave me one of their hooks, which I took as a curiosity. In it, the bone was fastened on by hemp, like that in France...Some of them came to us and begged us to go to their river. We weighed anchor to do so, but were unable to do so on account of the small amount of water, it being low tide, and were accordingly obliged to anchor at the mouth…1

Media

Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Discussion Questions

- What examples of Wampanoag daily life can you find on this map (ex. Houses, gardens, work, etc.) Which of these examples can you find in your community today?

-

What natural resources make Patuxet a good place for Wampanoag people to live?

-

What made Patuxet an appealing place for Europeans to trade and later establish colonies?

-

What does Champlain’s writing tell us about his first impressions of Patuxet?

-

How would a person living in Patuxet describe meeting Champlain for the first time?

-

Think about a time that you met someone whose cultural background was different from yours. How did you feel? Did those feelings change when you got to know them?

Footnotes

- 1 Samuel de Champlain, . Voyages of Samuel de Champlain: Volume 2. Trans. Charles P. Otis (N.p.: Outlook Verlag, 2018.), . 78. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.