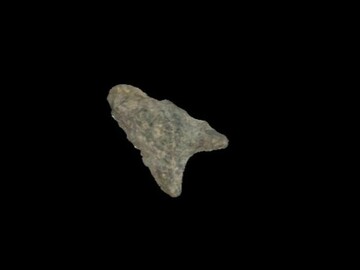

Postglacial Spear Point

Object ID: 19PL522.1977

- Date

- Early-Middle Woodlands Period (3,000-1,000BP)

- Material

- Earthenware

- Author/Maker

- Artist name is no longer known

- Source

- Plimoth Patuxet Museums Archaeology Collection

Description

More than 10,000 years ago (3,00-1,00BP)1, Indigenous peoples made points from rhyolite - an igneous, or volcanic, rock - to tip their hunting spears. Rhyolite is the ideal material for hunting spears due to its ability to keep a sharp point once knapped.2 Postglacial points like this one feature a long, leaf shape with a deeply concave base and shallow side notches for attaching the point to a wooden arrow shaft. This point’s edges show evidence of reworking, suggesting it was used enough to be worn down, re-sharpened and reused. This rhyolite point likely made its way from what is today Maine to Patuxet along ancient coastal trade routes.

As the Ice Age ended and the glaciers retreated 15,000 - 10,000 years ago, sea levels rose. The process transformed the landscape, separating what is most commonly known today as Cape Cod from the islands of Noepe (Martha’s Vineyard) and Notocket (Nantucket), which remain home to several Wampanoag communities. Today, the Aquinnah Wampanoag from Noepe tell stories of Moshup, a giant benevolent being, who created the islands. In an oral history interview, Aquinnah Tribal Educator Helen Manning recounted: “Martha’s Vineyard hasn’t been an island always. It was attached to the mainland so Moshup walked miles from what is now Rhode Island. When he was coming this way he could see this beautiful spot and so he decided that he would like to be here and take care of all the people who’d believe in him and he was so tired from walking miles he just dragged his big toe along the land and the land just went down and water rushed in and that’s when the island of Martha’s Vineyard was formed.”3

The changing landscape attracted giant Ice Age mammals such as mastodons, mammoths, and caribou and drew hunters northward from the south and west. Archaeology suggests that there were enough resources available to survive by hunting and gathering in a general area, moving to different places as the seasons, and needs for different resources, changed. The giant mammals died off about 8,000 years ago as global warming continued after the end of the Ice Age, and Wampanoag ancestors began to hunt smaller game including deer, elk, and moose.4More diverse foods became available and hunting technology improved. In 1643, Roger Williams commented in his Key into the Language of America:

The Natives hunt two ways: first they pursue their game, especially deer, which is wonderfully plentiful in this country. They pursue with groups of twenty, fourty, fifty, even two or three hundred hunters (as I have seen) pushing the game before them. Second they hunt with different types of traps…which he baits with food the deer loves. He walks his territory to view his traps every other day.5

In addition to food, Wampanoag men and women use animal hides and sinew to make clothing, bags, and other household items. Bones became toys and tools, including sewing needles and fishing hooks. Men cover their bodies in rendered animal fat to keep warm in the winter and keep away biting insects during the summer. Hunting remains an important source of gathering food for Wampanoag families. In the 2019 edition of AKey into the Language of America (1643) published by the Tomaquag Museum, Narragansett cultural leaders added to Williams’ observations:

Today in our community, there are many hunters. They hunt with traps, bow and arrows, and guns…intergenerational families hunt together, pushing, tracking, and harvesting the game. It is our custom to share the harvest with all families represented in the hunting party as well as elders, the sick, and others in need.6

Plimoth Patuxet Museums’ Indigenous Educators maintain, “in the Wampanoag way of life, all Beings on Earth were given gratitude for their existence and for their gifts. All of the Nations of Animals, Winged Ones, Water Beings, even the tiny insects were considered to be gifts from Creator to the Humans. Everything had its purpose. All life is considered sacred, and treated that way.”7

Media

Touch the screen or use your mouse to manipulate the archaeological artifact. What do you notice when you look closely?

Discussion Questions

- What does this object tell us about how people lived in Wampanoag homelands 10,000 years ago?

-

How does Wampanoag life 10,000 years ago compare to life in the early 1500s (just before the Wampanoag first encountered Europeans in their homelands)?

-

What do you think it would be like to use a spear to hunt during the Ice Age?

-

How has Wampanoag hunting changed since this point was made?

-

What is an example of something you reuse?

Footnotes

- 1 BP refers to “Before Present” or “Before Present Time.” This is a time scale commonly used in archaeology, geology, and other sciences to specify when events occurred relative to the invention of radiocarbon dating technology in 1950. To determine the actual age of an artifact subtract its date in years before present from 1950.

- 2“Rhyolite,” Wikipedia. Accessed 10/5/23.

- 3 “Helen Manning - Moshup creation of the Island.” MV Museum Oral History Channel. Youtube.

- 4 Neal Salisbury, Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the Making of New England, 1500-1643 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 14

- 5 Williams, A Key into the Language of America Tomaquag Museum Edition. Dawn Dove, Sandra Robinson, Loren Spears, Dorothy Herman Papp, and Kathleen Bragdon, ed. (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2019), 146

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 Nancy Eldridge, “Who are the Wampanoag?” Plimoth Patuxet Museums. Accessed 10/5/23.